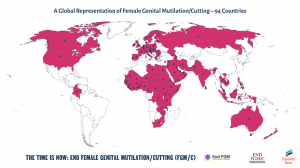

NEW YORK, NY, UNITED STATES, February 26, 2025 / EINPresswire.com / -- A new report has compiled evidence of female genital mutilation (FGM) also known as female genital cutting or ablation in 94 countries, revealing how this harmful practice exists in more communities than previously

recognized and how the number of girls and women affected or at risk exceeds previous estimates.Efforts to end FGM continue to be hampered by government resistance to act, particularly in countries not widely associated with FGM. Other obstacles include weak legal protections, lack of data, low awareness, lack of funding, and a lack of decisive action by the international community.

“The Time is Now: Ending Female Genital Mutilation – An Urgent Need for a Global Response – Five-Year Update,” by the End FGM European Network, Equality Now and The US Network to End FGM/C, compiles evidence on the nature and practice of FGM in different countries. Small-scale surveys, estimates and personal testimonies from survivors, activists and grassroots organisations shed new light on the urgent need to scale up protection and prevention efforts.

The research follows up on the group’s 2020 report , which documented how the scale of FGM was being woefully underestimated globally. Since then, FGM has been identified in local communities in Azerbaijan, Cambodia and Vietnam, and further evidence has been gathered in Colombia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Sri Lanka and the United Arab Emirates. Further research is required where data is limited, such as in Panama, Mexico and Peru, where FGM may exist among indigenous groups.

“The mounting evidence clearly shows that FGM is a global problem that demands a coordinated global response,” said Divya Srinivasan of Equality Now. “To end FGM, governments, international agencies and donors must recognise the scale of the problem, strengthen their political commitment to address it and prioritise funding, especially in underserved regions and communities.”

ENDING FGM REQUIRES BETTER DATA AND MORE FUNDING

In 2020, UNICEF estimated that at least 200 million women and girls had undergone FGM in 31 countries. In 2024, UNICEF updated the figure to more than 230 million—80 million in Asia, 6 million in the Middle East, and 1–2 million in small communities or diasporas elsewhere. The 15% increase in UNICEF’s estimate is due to the incorporation of newly available data from countries previously excluded from official statistics, combined with rapid population growth in regions where FGM occurs.

While UNICEF’s 230 million figure is the first comprehensive global estimate of the number of women and girls affected, detailed data on national prevalence is only available for 31 countries. This lack of data allows reluctant governments to continue to avoid recognizing or addressing FGM.

The majority of international funding is focused on a few African countries. While this work to end FGM is severely underfunded and requires increased investment, the lack of funding is even more acute in Asia, Latin America and the Middle East, which receive only a small allocation.

The problem is compounded by the fact that some governments do not recognise FGM in their countries and in some cases actively deny it, undermining and sometimes openly discrediting the work of survivors and activists.

Comprehensive data is crucial because it provides evidence on the need for action and funding, and sets a baseline from which interventions can be developed, implemented, monitored and evaluated.

Tania Hosseinian of the End FGM European Network explains: “Access to accurate and up-to-date data is crucial to understanding the full scale of FGM and to developing and evaluating laws and policies that ensure no one is left behind. Data-driven strategies must guide our actions, empowering grassroots organisations, youth movements and survivors to lead the way.”

MANY COUNTRIES STILL DO NOT HAVE SPECIFIC LAWS AGAINST FGM

FGM is internationally recognised as a serious human rights violation that involves the partial or complete removal of the external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. It is rooted in gender inequality and attempts to control the bodies and sexuality of women and girls.

FGM has no health benefits and can cause serious short- and long-term harm. Potentially fatal – as tragically demonstrated by FGM-related deaths in Sierra Leone and Kenya in 2024 – it is associated with numerous health problems including chronic pain and infections, psychological trauma, infertility and higher maternal and infant mortality rates.

Despite this, of the 94 countries where FGM has been found, only 58 (61%) have laws explicitly prohibiting it. This leaves millions of people without adequate protection and allows perpetrators to avoid accountability.

Since 2020, India, Jordan, Kuwait, Singapore, Sri Lanka, the Russian Federation, the United Arab Emirates and the United States have received recommendations from international human rights mechanisms calling on them to take greater action to address FGM.

Positively, in 2020, only 51 countries specifically prohibited FGM. Since then, Sudan, Indonesia, Finland, Poland and the United States have passed federal laws, while France has strengthened its penal code, and the European Union has adopted new regional legislation.

Several countries have achieved reductions in FGM rates, including Burkina Faso, Liberia and Kenya, among others, while Portugal, Gambia and the United Kingdom have seen the first successful convictions for FGM.

MEDICALIZATION OF FGM AND OTHER THREATS TO PROGRESS

Worryingly, the backlash against women’s rights threatens to undo hard-won gains. In Kenya and Gambia, legal challenges have attempted to repeal existing anti-FGM laws, threatening to reverse years of progress. These regressive attempts have been met with determined resistance from women’s rights activists, legal experts, journalists and international partners collaborating locally and internationally to prevent backsliding.

Another concern is how medicalization is becoming more commonplace. UNICEF’s 2024 report found that 66% of girls who recently underwent FGM did so at the hands of a health worker. In countries such as Egypt, Indonesia and Kenya, medicalized FGM is wrongly perceived by some as a legitimate alternative, while in Russia, it is openly promoted by clinics.

There is growing awareness about practices that are not yet formally recognized as forms of mutilation. This includes the “husband stitch,” when an extra stitch is added during vaginal repair after childbirth, with the purpose of narrowing the vaginal opening to increase the sexual pleasure of the male partner. Often performed by medical professionals without the consent of the woman, recent research has found cases in Europe, Japan and the United States, with survivors experiencing health complications and comparing this to FGM.

PUTTING WOMEN AND GIRLS AT THE CENTRE OF EFFORTS TO END FGM

Ending FGM requires a global but nuanced strategy that addresses the specific ways it is practiced in different regions and communities. With Sustainable Development Goal 5.3 setting 2030 as the target for ending FGM, there are only five years left to accelerate and globalize efforts.

Transformative social change requires a collaborative, multifaceted, survivor-centered approach that incorporates the enactment and enforcement of strong legal protections alongside community engagement to raise awareness of the harms of FGM and its legal consequences.

Caitlin LeMay of The US End FGM/C Network concludes: “Millions of people around the world live with the lifelong consequences of FGM. Their courage in sharing their stories has brought global attention to this harmful practice and strengthened the movement to end it.”

“Survivors, wherever they live, must have access to adequate, affordable and quality services that are gender, child and culturally sensitive, ensuring that their voices remain central in the fight against FGM.”

No comments:

Post a Comment